Football was once a violent game on and off the pitch, but the sport has cleaned up its act for the good of players and spectators. Here, Steve Rogerson looks at that period of change from the 1970s and 1980s to the modern game were the hooligans have been marginalised and the terraces have become safer.

How football has lost its violent past

How aggression in football has been channelled into skill not hooliganism

Football fans enjoying themselves rather than fighting Photo by Steve Rogerson |

Let’s face it, quidditch as made famous by the Harry Potter books, is a really silly game, not least because of its ridiculous scoring system. There is, however, a rather unusual element of quidditch that has more of a reflection in real sport, and that is the legalised gratuitous violence. This takes the form of bludgers – large heavy balls – and beaters – players with sticks who try to hit the bludgers at opposing players, which when successful often ends up in serious injuries. This mirrors a view of sport that grew up in the 1960s and 1970s that the more violent it would become the more interest it would have for spectators.

This can be seen in the USA, where its version of rugby known as American Football or gridiron is really made up of a series of gladiatorial set-plays. This carried forward into other US sports as typified, for example, in the film Slap Shot in which a struggling ice hockey team manages to turn its fortunes around by becoming more violent.

In the movies

Taking this idea a step further was the film Rollerball. Here the rules were changed constantly to make the sport more violent and thus win more viewers, with the subplot that the last thing the corporations running the game wanted was a hero, so the more violent it became the less chance there was of anyone surviving more than a few games and thus achieving hero status. Those who have seen the film know that this didn’t quite go to plan.

Here though there was still the resemblance of a game to create a structure to the violence. There later followed a number of films in which the violence became the point of the game, the Japanese film Battle Royale perhaps being the most famous. In the movie, a class of schoolchildren were armed and placed on island. The winner was the last one alive.

Football in England

Now, it is unlikely that any sport will evolve quite to that level, no matter how dysfunctional a future society becomes. What is pleasing though is the progress the English national game has taken during this same period. In 1975, when Rollerball came out, football was a violent game both on and off the pitch. Harsh, crippling tackles were the normal reward for anyone showing a modicum of skill on the pitch, and gangs of rival fans punching the daylights out of each other became a regular sight on the terraces and in the areas surrounding the football ground.

With the state of the game as it was, it was no surprise really that film and book writers portrayed an even more violent future for sport. And when the powers that be set about cleaning up the game, it was met with howls of protest about how this was a “man’s game” and that if you removed the physical battle then people would stop watching.

They were proved wrong. The clamping down on the worst aspects has allowed skills to flourish and brought a much more exciting spectacle. True, the game is still physical, and so it should be, but it is for the most part clean with digression punished quickly. This has been mirrored by a more friendly rivalry between fans, with much of the hooliganism now a thing of the past.

True, you still get the odd incident, but such disgraceful goings on are now the exception rather than the rule. And as for the pundits who predicted people would stop watching, the crowds today are for the most part higher than they were in the early 1980s. True, sport has to stay competitive, but football is proving that it doesn’t have to be violent.

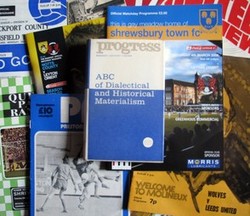

See also Changing Fashions of English Football Fans and Dialectical Materialism in Football.

You might also like

Dialectical materialism and footballThe process of change and the effects of change on popular sport.

Changing fashions of English football fansFrom rattles and rosettes to team shirts, how fashions have changed since the...

KZine Issue 31: Review of October 2021 Issueon 11/07/2021

KZine Issue 31: Review of October 2021 Issueon 11/07/2021

KZine Issue 30: Review of June 2021 Issueon 07/05/2021

KZine Issue 30: Review of June 2021 Issueon 07/05/2021

KZine Issue 29: Review of February 2021 Issueon 02/23/2021

KZine Issue 29: Review of February 2021 Issueon 02/23/2021

KZine Issue 28: Review of September 2020 Issueon 10/01/2020

KZine Issue 28: Review of September 2020 Issueon 10/01/2020

Comments

SteveRogerson, Thank you for product lines, pretty pictures and practical information.

This is an eye-opener of an article. I never knew that polite Brits were violent on the playing field (or playing ice ;-D). Somehow I only knew about soccer fans -- unlike my experience in Brazil, where soccer games no matter the outcome inspire friendly, happy samba in the streets -- misbehaving after a game. Would this hold for criquet?