Leon Trotsky is viewed by many as not only one of the great thinkers in Marxist history but an independent voice that was willing to challenge accepted theories. This often brought him into conflict with other revolutionaries. One of the planks of his thinking was his theory of permanent revolution, but how did that theory hold up when faced with actual revolutions in Russia, China and Cuba?

Leon Trotsky’s Theory of Permanent Revolution

A look at Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution and how it stood up in practice in Russia, China and Cuba

Leon Trotsky’s Theory of Permanent Revolution |

One of Leon Trotsky’s major contributions to Marxism was his theory of permanent revolution. This grew from his experience of the 1905 revolution in Russia when at the time the dominant position among Marxists was that a socialist revolution could not be obtained in countries that did not have a large and mature working class. The feeling among all sides on the Russian left at the time was that Russia was ready for a bourgeois revolution and only after that could a socialist revolution be possible.

The Mensheviks saw the bourgeoisie as leading the revolution and taking political power into their own hands. Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks disagreed with this position and looked instead to an alliance of the working class and peasantry to create a bourgeois revolution and only then would a working class revolution be possible.

Trotsky disagreed with both these positions notably with Lenin about the ability of the peasantry to be an independent revolutionary force. He believed the working class in Russia, though small, was capable of carrying out a socialist revolution that could become permanent but only if the correct actions were taken and that the revolution spread internationally. Lenin was eventually won over to this view.

Theory of Permanent Revolution

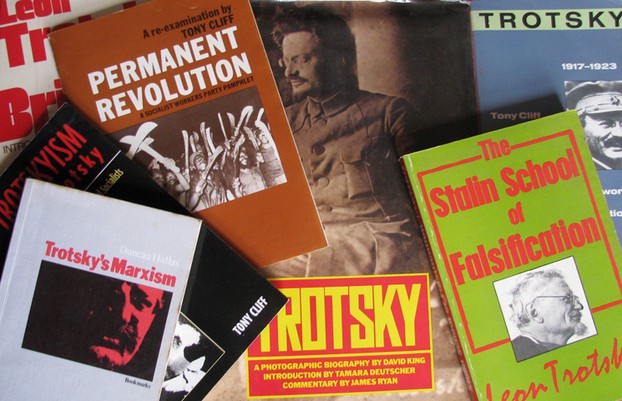

The Marxist Tony Cliff summed up Trotsky’s theory in his pamphlet “Permanent Revolution: A Re-Examination”. He broke the theory down into six points:

- A new bourgeoisie has not the same revolutionary capabilities as those a century or so previously in that on its own it is not capable of destroying feudalism and establishing a political democracy.

- The working class has to lead the revolution, even if it is small and underdeveloped.

- The peasantry are incapable of independent revolutionary action and must follow the working class.

- A bourgeois democratic revolution must move over to the socialist revolution to become permanent.

- Revolutions in backwards countries will lead to upheavals in the advanced countries.

- The revolution cannot survive isolated in one country; to become permanent it must become international.

Russia 1917: Permanent Revolution Put to the Test

The 1917 revolution in Russia proved to many the correctness of Trotsky’s theory, though not all in a positive way. Taking the six points above, this is how the events unfolded:

- The bourgeoisie was a counter-revolutionary force.

- The industrial working class led the revolution.

- The peasantry followed the working class.

- The anti-feudal, democratic revolution moved over immediately to a socialist revolution.

- Revolutionary convulsions followed in Europe, notably in Germany, Austria and Hungary.

- The isolation of the revolution in Russia led to its failure and the rise of Stalinism.

China and Cuba: Setbacks for the Theory of Permanent Revolution

Whereas the Russian revolution seemed to prove Trotsky’s theory, the rise of Mao in China and Castro in Cuba appear to disprove it.

In China, the industrial working class were not involved, in fact during the revolution itself the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party were stifling workers’ unrest.

The situation of Fidel Castro taking power in Cuba involved neither the working class nor the peasantry but was led almost exclusively by middle-class intellectuals.

The problem for Trotsky’s theory in both these cases is point two above. Whereas the working class can lead a revolution, its political development may be such that it has neither the will nor ability to carry out that role. Without that, the third point also falls as there is no working class for the peasantry to follow.

Deflected Permanent Revolution

Tony Cliff argued that Trotsky’s theory needed amending in that when the working class was unable for whatever reason to take the role envisaged by Trotsky then sections of the intelligentsia could lead a revolution but this revolution by its nature would not be socialist but bourgeois in concept. What they created, he believed, was what he called state capitalist societies, and despite their own terminology that was in fact what China, Cuba and, as well, Russia under Stalin became.

Sources

- “Nasha Revoliutsija” by Leon Trotsky, 1917

- “Permanent Revolution: A Re-Examination” by Tony Cliff, Bookmarks Publications, 1983

- “Deflected Permanent Revolution” by Tony Cliff, International Socialism 1963

- “Permanent Revolution” by Chris Bambury, Socialist Worker, 27 August 1983

You might also like

Dialectical materialism and footballThe process of change and the effects of change on popular sport.

English Radical Writing in the 1790sThe French Revolution inspired English radicals to dare to fight for reform. ...

KZine Issue 31: Review of October 2021 Issueon 11/07/2021

KZine Issue 31: Review of October 2021 Issueon 11/07/2021

KZine Issue 30: Review of June 2021 Issueon 07/05/2021

KZine Issue 30: Review of June 2021 Issueon 07/05/2021

KZine Issue 29: Review of February 2021 Issueon 02/23/2021

KZine Issue 29: Review of February 2021 Issueon 02/23/2021

KZine Issue 28: Review of September 2020 Issueon 10/01/2020

KZine Issue 28: Review of September 2020 Issueon 10/01/2020

Comments

SteveRogerson, Thank you for practical information, pretty pictures and product lines.

This is an excellent analysis of China, Cuba and Russia. Would you happen to have seen the film Che by Steven Soderbergh?