As we leave Maelgwn entering those remote monastic caves, a vivid picture of the young man can be formed.

As we leave Maelgwn entering those remote monastic caves, a vivid picture of the young man can be formed.

We know that he was well educated. Gildas makes a point of saying so, stating too that Maelgwn's schooling was Roman in nature.

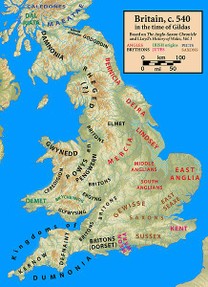

Archaeologically, Gwynedd has been proved to be a bastion of Romano-British society during this time. Monuments continued to be erected, as they were during the Roman Occupation.

St Illtyd wouldn't have bothered intervening, if Maelgwn didn't matter. That the saint traveled such a distance suggests he considered Maelgwn's actions - and religious affiliation - to be of utmost consequence to the whole of Britain.

Of course, Maelgwn came from a powerful family. As the son of Cadwallon Lawhir, and the nephew of Owain Danwen, he was part of an important dynasty, ruling over large territories in Celtic Britain. He could (and would) one day be chieftain himself. That made him influential, either indirectly via his family, or directly due to his own demonstrable strengths as a person.

Maelgwn was undoubtedly a great military leader, even as a youth. Three times, in a mix of history and myth, his intervention as a warrior is tied to the outcome of a battle.

- As the King of a Hundred Knights, in the Arthurian legend, he's credited with ensuring victory for the Celts at Badon.

- As the murderer of his uncle, Maelgwn's warband defeated that of a king.

- As an erstwhile ally at Camlan, the fact that he sat on the sidelines was seen as the reason that Arthur was killed.

There's also the fact that Maelgwn COULD raise enough men to fight under his command, at least in Badon and against his uncle. The young man wasn't a ruler then. Those men riding under his banner must have been answerable to his father instead. Yet they came anyway.

Charismatic and intelligent, there's one last facet to apply, which allows a glimpse into his mind.

Maelgwn seems highly sensitive to spiritual concerns. If he did switch to Pelagianism or Druidism, then he cared about religion enough to question his conscience and convert. Moreover, he listened to St Illtyd. He didn't have to. He could have laughed in his face, like Vortigern did when St Germanus came to preach against a similar faith conversion. Or he could have had Illtyd kicked from Gwynedd - it's not like Maelgwn didn't have the manpower to enforce such a banishment.

Instead, Maelgwn heard what Illtyd had to say, considered it long and hard, then vowed to enter a monastery. That wasn't lightly given. By taking holy orders, he effectively removed himself as ruler of whichever territory he'd gained by killing his uncle; cut himself out of the running as future ruler of his father's lands; gave up his wife; and denied himself the right to raise his own infant son.

Mind you, it didn't last. The instant that his father died, Maelgwn was out of the monastery and seizing control of Gwynedd. Bigger, meaner, stronger and self-advancing as ever.

But those are stories that will be told in part two.

Maelgwn (pron.

Maelgwn (pron.

It's at this point that myth and/or half-remembered history merge, into a tale that's latched onto the Arthurian legends.

It's at this point that myth and/or half-remembered history merge, into a tale that's latched onto the Arthurian legends.

As we leave Maelgwn entering those remote monastic caves, a vivid picture of the young man can be formed.

As we leave Maelgwn entering those remote monastic caves, a vivid picture of the young man can be formed.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Jon - Thank you very much! That one was puzzling me.

Gwall wen= white hair

Gwall gwyn= white hair

I always assumed that Maelgwn only went into the monastery to escape Illtyd.

I didn't realize that you were actually in a monastery too. I knew that you were nearly ordained as a priest, but not that you were a monk.

I totally agree re Gildas. He's all we have for certain things, but he's also the REASON that he's all we have. And that sermon is horrific, when you look at it. Plus you notice that he's not upsetting anyone on his side of the Channel, only the five rulers who can't get to him.

Can you blame Maelgwyn for coming out of the monastery? I left,, and have never regretted it. Catholicism does not blame anyone who levaves before ordination.

Gildas is a historical disaster. His historical account was primarily theological, and a great untruth ensued.

It's the Arthurian legend and 6th century Celtic history, we're all missing 99% of the details. Some of that is down to Gildas, who did a lot of destroying manuscripts in various places, if he didn't like the people mentioned. Incidentally, he apparently hated Arthur, which is one reason that some think we have little contemporary information about him.

I'm feel like I'm missing 99% of the details >.> Even in that super detailed one you wrote.

Agreed on all counts, hence me ensuring that I only wrote Saxons during that battle. But thanks for spelling it out for those who come afterwards. I sometimes get so caught up in the nitty-gritty, that I forget that the majority of people don't know every available detail of Badon!