There's no doubt that the Landon family was in financial difficulties, when Letitia began her writing career. Her personal letters reveal an on-going drive to keep herself economically solvent throughout the next eighteen years.

There's no doubt that the Landon family was in financial difficulties, when Letitia began her writing career. Her personal letters reveal an on-going drive to keep herself economically solvent throughout the next eighteen years.

Yet she was one of the most highly paid poets of the period, at a time when they were the foremost major celebrities. So what on Earth was happening to all of the money?

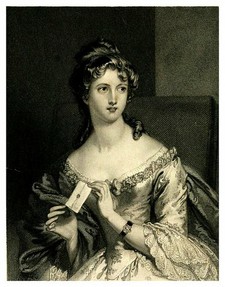

It's been estimated that L.E.L. earned around £2585 throughout her career.

That doesn't seem a lot for nearly two decades of churning out words in ceaseless working. But that's because it's not adjusted for the Georgian period.

In order to reach the equivalent amount in today's money, the figure needs to be multiplied by 250. Which means that L.E.L. actually earned approximately £646,250, or roughly £36,000 a year.

Suddenly not too shabby, is it? Though please do note that it's notoriously difficult to compare wages and living costs across the centuries. The above should be considered approximate figures.

L.E.L. was in the perfect position to be independently wealthy. A Georgian woman able to keep her own house, providing for all of her own needs without resource to male relatives. To some extent, this was true.

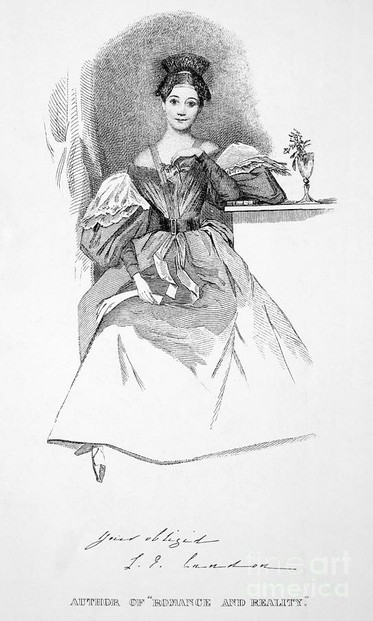

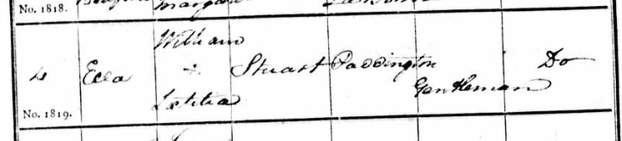

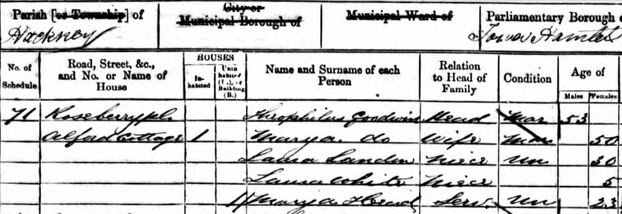

Following her father's death in 1824, she moved out of her parents' home to live with her maternal Grandmother Bishop. That could well have been a comfortable situation, as Letitia Bishop lived on independent means of her own. (William Jerdan suspected that the Welsh lady was the 'natural' - i.e. illegitimate - daughter of an aristocrat, though that was never confirmed to him or anyone.) Letitia and her namesake were extremely close, but the older lady could never quite get her head around the fact that L.E.L. shouldn't be disturbed while working.

In 1827, Letitia Landon returned once more to 22 Hans Square - now sadly devoid of Mrs Rowden, who'd gone to France to be Fanny Kemble's governess. This time, Lettie was not a student, but a boarder. She rented her old bedroom, on the top floor, for the next decade.

But beyond that perceived - and by contemporary standards, scandalous - extravagance, L.E.L. seemed constantly impoverished.

There's no doubt that the Landon family was in financial difficulties, when Letitia began her writing career. Her personal letters reveal an on-going drive to keep herself economically solvent throughout the next eighteen years.

There's no doubt that the Landon family was in financial difficulties, when Letitia began her writing career. Her personal letters reveal an on-going drive to keep herself economically solvent throughout the next eighteen years.

Once news of the death of L.E.L. reached London, the gossip mills practically exploded under the frenzy of speculation.

Once news of the death of L.E.L. reached London, the gossip mills practically exploded under the frenzy of speculation.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

It's a pity the only living rocket scientist at the time of Letitia's death was ignored. He pointed out that if she had been poisoned she could not have been clutching the phial. In fact there was no evidence she had actually taken any medication. A sensible response would have been to ask why she was using it and why she told her husband her life depended on it. Merely to obtain a denial from her doctor that he had prescribed it was hardly sufficient. It seems clear she must have consulted a specialist. Anyway it does seem probable she was aware that her life was in danger.

I was so hoping that you'd run with the medical side of this, as I know you have much more insight into it than me.

You'd also be amazed at what you could buy over the counter back then. As late as the early 20th century, no-one blinked at people walking into a Chemists (Drug Store in your 'hood) and buying quantities of arsenic or cyanide. Prussic Acid really does appear to have been readily available in 1838; moreover, it was part of a remedy for heart palpitations.

You might find Julie Watt's take on the death of L.E.L. quite informative: http://www.academia.edu/4127697/Letit... It begins with a look at how L.E.L. describes her exact death in her final novel, then goes onto the chemistry side of things.

It was just a thought I had.

Another thing, you mentioned that she would've had the prussic acid for a heart problems, but couldn't find info on that anywhere. Even if it wasn't an accident, I do think the prussic acid had to have come from somewhere, right? Unless it was a thing otherwise easily obtained. If it was murder, then perhaps the murderer had some on hand, but if it wasn't something she already had on hand, wouldn't it have stood out to her husband or at least the doctor as odd that she had the prussic acid if they hadn't already known it was something she had, right?

Oh! You've commented again while I was responding to the other one. :)

So you're going with suicide then? It is the top theory amongst those looking at the story. I'd like to get my hands on Michael Gorman's book, as the murder one is the only theory I haven't fully explored yet. Personally the jury is out here.

Your take on the suicide personality was interesting. I didn't know that. I was just reporting the facts, as they we reported at the time. Elizabeth seemed in some shock about how jolly those letters were, but her response to L.E.L.'s poem makes it clear what she privately thought happened.

She really was quite influential. The further I dug, the more I'd find where she'd inspired a much more famous later poet. I kept stopping, re-evaluating - am I projecting this onto her, because I want her to be that influential? Then I'd catch an obviously derivative line in Poe, or read a critic telling the young Tennyson to stop copying L.E.L. wholesale, and I had to stop being so hard on her.

You've just hit the nail on the head as to one of the major reasons that I found Letitia so fascinating. Soooo much information, and so few definitive conclusions. It's obvious why.

Here's a lady who often had to live a lie in order to retain her position in the public eye. If she wasn't popular - and therefore remained the picture of someone who could be popular - then the bills weren't being paid. She must have muddied a lot of waters to keep that one up. In addition, here is a lady whom a lot of people had a stake in presenting a certain way. Often the true facts were mere suggestions amongst a raft of options in telling her life story, at least for the contemporary biographers.

Which all leaves us with a bit of a mess. I do enjoy sifting through a cascading jumble of facts, in order to find those things which can be verified and put together to tell a story, as close to the truth as we can get.

:D

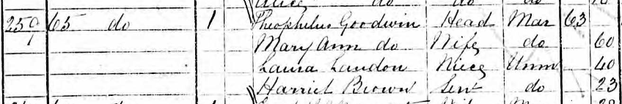

I haven't fully looked into the three children yet. Cynthia Lawford's work is stuck in the University of NY, so I haven't been able to read it. I'm planning to recreate it though, to see what I think. But first I'm sorting out her cousin's family. I spent hours last night, following a major break-through in finding both Thomas Silvanus Landon AND Anne Lane in the 1841 census - different houses, loads more kids than I knew about before.

I will say I didn't expect that her life ended in any sort of tragedy. But when I was reading and you kept repeating how happy she said she was I knew something was coming. It reminded me of my first year of high school. There were actually a lot of suicides, there was one, then another with a note saying the first inspired it, and then two more which were not technically related to the first two but the school said they were. The school was scared, obviously, and we had several school wide and smaller meetings about suicide, in which we learned the warning signs and a lot of other info. I think the one 'warning sign' that has always stood out to me the most was described as perhaps the most dangerous, for multiple reasons. It was sort of described as 'you may notice your friend has stopped worrying about things, big things, little things, especially things that maybe always bugged them in the past that just don't anymore. They may described to you feeling a sense of peace or new found happiness.' I remember they explained it as dangerous because you may be thinking, look here my normally quite shy, or anxious, or depressed etc. friend is so happy, I'm happy for them. Like, your first thought isn't, my not-normally happy friend is happy, they're probably suicidal, but it is also considered dangerous because that stage hits when the decision is made, and the planning is done. They know they're going to kill themselves, they know how, and when, and they're completely at peace with it.

So it stood out to me when you talked about her writing home and being happy, sharing a gift with a friend, something like that doesn't normally come across quite so forebodingly as it did here, I suppose.

I loved the intro, she seems to have been mentioned by a lot of famous poets.

Honestly, this part of the three was very fascinating. The big theme in all of them is just how much speculation there is about her life--all the way up until the end of it, I really didn't expect that bit. I don't know why it is so weird to me that we know so much yet so little about her. It is, in a way, really quite amusing, that's a bit of what you were getting at with all of the varied accounts of her biography isn't it? I'm guessing there are theories which you favor in each case.

And, of course you are related to a famous Welsh writer! :O

What are your thoughts, as a genealogist, re the bit with her potential offspring?