Fellow Men,

I am not an Irishman, yet I can feel for you. I hope there are none among you who will read this address with prejudice or levity, because it is made by an Englishman, indeed, I believe there are not.

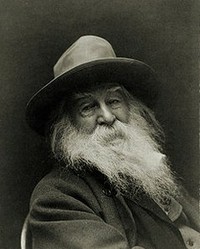

An Address to the Irish People by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Shelley was not stupid. He knew from the out-set that an English accent in Ireland was not going to be trusted.

This was February 1812. Just over a decade before, Ireland had been forcibly dragged into the United Kingdom. The United Irishman Rebellion of 1798, and Robert Emmet's uprising in 1803, had been brutality put down. In forty years time, the English would attempt an Irish genocide, after the potato crops failed.

In short, the Irish people were very well aware of the issues of social repression, which Shelley was so passionate about. The realities of Dublin made the poet realize that he too had been a woefully ill-informed 'fireplace revolutionary'.

He immediately wrote two more pamphlets. Proposals for an Association urged all of the disparate Irish rebels to come together under a single banner. They could defeat their British oppressors that way. (This eventually proved true after the Easter Rising a century later.)

Declaration of Rights was even more far-reaching and radical. It set out thirty-one points for the reform of society. They included many of the articles which would find fruition in Queen Mab. It laid out the fact that all human beings, regardless of class, nationality or religion, already had rights. It was their duty to fight to ensure that they were able to exercise them.

While Shelley wrote, Harriet took to the streets, handing out the pamphlets and pinning them to walls.

The couple began arranging public meetings all over the city. Shelley addressed packed halls with impassioned speeches. The rhetoric appears to have been very well received. Everyone cheered, clapped and hissed in all of the right places.

But that did not mean that any Irish man or woman was about to march under the banner of an English teenager. Especially not when their own political leaders, like Daniel O'Connell, were speaking in the same meetings.

However, they had impressed one young revolutionary. Dan Healy began helping Harriet distribute the pamphlets. He was enamored enough of Shelley's ideals, that he later accompanied the couple back to Britain.

It was while they were living in Dublin (at 17 Grafton Street), that the Shelleys became vegetarians. It was called the Pythagorean system; and it would have been downright radical at the time.

They were only in Ireland for seven weeks. The impetus to come back was in a letter from William Godwin. He'd read Shelley's Declaration of Rights, and heard about their activities, and he was appalled.

It wasn't the content, it was experience. He could see, better than Shelley, what revolution in Ireland would truly look like. It would be a massacre! Godwin wrote that the couple were 'preparing a scene of blood' and that this wasn't the answer.

Idealistic Shelley was also a pacifist. He hadn't quite grasped how bloody the fight would be. He trusted and believed Godwin, and immediately told Harriet that they were leaving.

Percy Bysshe Shelley thought that he was dying. He had been ill for some weeks and it seemed to him that his mortality was dripping away.

Percy Bysshe Shelley thought that he was dying. He had been ill for some weeks and it seemed to him that his mortality was dripping away.

To say that Shelley was interested in politics and social reform is a bit of an understatement. It fired up his life in the winter of 1811 and spring of 1812.

To say that Shelley was interested in politics and social reform is a bit of an understatement. It fired up his life in the winter of 1811 and spring of 1812.

Before we move on to rabble rousing in Eire, it's worth pausing at a curious incident in Rheged.

Before we move on to rabble rousing in Eire, it's worth pausing at a curious incident in Rheged.

In early April 1812, the Shelleys, along with Elizabeth Westbrook and Daniel Healy, crossed the Irish Sea to Holyhead in Wales.

In early April 1812, the Shelleys, along with Elizabeth Westbrook and Daniel Healy, crossed the Irish Sea to Holyhead in Wales.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

I love him! A true wild child of the poetical world. But I'm also not rose-tinted about him. How he treated Harriet Westbrook was appalling.

Glad you liked this though. I am planning a follow up, with how Queen Mab was received.

Jo, a very informative and interesting page very well put together. Shelly is one of my favorite poets and historical characters. I always found him and those around him intriguing. Outstanding page!

If you want to PM me your ancestry, I can see if I can help. There's a slight problem with a Dublin ancestry though, in that many records were destroyed during the war. :( Hopefully your family's survived intact.

And always good to hail a fellow Celt!

Wow, I've got to read this again. We just found out that my gg grandfather was from Dublin. Now I've got to learn all the Irish stuff. I always wondered who Queen Mab was.