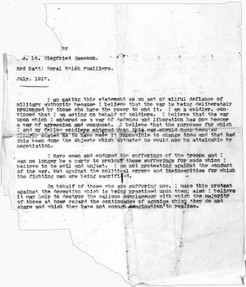

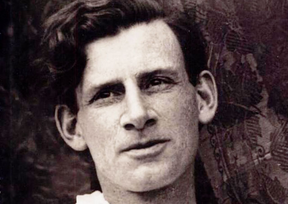

Inconvenient truths in poetry and uncomfortably strange heroics were one thing, but in 1917, Siegfried Sassoon crossed a line that the British government could not easily overlook.

Inconvenient truths in poetry and uncomfortably strange heroics were one thing, but in 1917, Siegfried Sassoon crossed a line that the British government could not easily overlook.

Devastated by yet another death - this time his friend David Cuthbert - and egged on by philosopher Bertrand Russell, Sassoon suddenly embraced the tenets of pacifism.

He threw the ribbon from his Military Cross into the River Mersey. Then found a depressing symbolism in the fact that it was too lightweight to sink in those mighty tidal waters.

In a letter sent to his commanding officer, and read out in the House of Commons, he accused the British establishment of secret hawkishness.

Government and generals alike were prolonging hostilities unnecessarily, at the cost of millions of lives and misery. They were peddling 'a war of defence and liberation', which was really one of 'aggression and conquest'. In consequence, Sassoon wrote that he was 'finished with the war' and hereby resigned his commission.

Had he been anybody else, Siegfried would have risked court martial. The penalty for which ranged from imprisonment with hard labor through to being shot at dawn. There were certainly isolated MPs irritated into calling for the latter.

But cooler minds prevailed, spelling out precisely the dilemma which David Lloyd George's government now faced.

Siegfried Sassoon was just too popular, too well-known. He was a decorated hero, who had exhibited startling courage under fire. His poetry touched chords in the national psyche, which no politician could ever hope to achieve.

If punished, they risked a backlash from the British population. If left unchecked, there was a strong possibility that the poet's talent could be used to further the arguments of pacifism, while undermining public trust in the government.

For a moment there, it seemed that the former was the lesser of two evils.

His friend, and fellow poet, Robert Graves came up with a solution. To the annoyance of Siegfried himself, the suggestion was made that he was suffering from shell-shock. The panicking British government immediately grabbed the compromise. Sassoon was sectioned and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers, as if he really was thus afflicted.

While Sassoon's brand of lyrical realism made him the darling of those living the literal reality, it understandably rendered him a thorn in the side of the War Office.

While Sassoon's brand of lyrical realism made him the darling of those living the literal reality, it understandably rendered him a thorn in the side of the War Office.

Inconvenient truths in poetry and uncomfortably strange heroics were one thing, but in 1917, Siegfried Sassoon crossed a line that the British government could not easily overlook.

Inconvenient truths in poetry and uncomfortably strange heroics were one thing, but in 1917, Siegfried Sassoon crossed a line that the British government could not easily overlook.

Siegfried Sassoon was discharged in February 1918, but initially posted with the British Army in Palestine. He didn't make it back to the front line in France until July of the same year.

Siegfried Sassoon was discharged in February 1918, but initially posted with the British Army in Palestine. He didn't make it back to the front line in France until July of the same year.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Thank you for reading it, and I'm glad that you enjoyed it.

I loved this page, Jo, and enjoyed his poems.

I'm glad that you liked it. :) And yes, I thought he was incredibly interesting.

This is a very interesting article about a very interesting man!

The sarcasm of that poem absolutely bites, doesn't it?

Ordinarily, I'd be nodding away in agreement regarding mental institutions of this period. But Craiglockhart was hugely ahead of its time. Under the leadership of Dr Rivers, a whole system of treating trauma psychology was devised, which still largely holds in place to this day.

I liked Does it Matter. Artists have beautiful minds.

But also- "and put him safely away in a sanitarium" ...safely... LOL