Sydney Harbour Bridge

by lou16

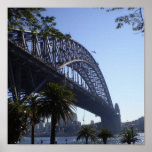

The Sydney Harbour Bridge has become an iconic Australian landmark since it was completed in the 1930s. Let’s look at the Sydney Harbour Bridge in more detail.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge

Affectionately Called The ‘Coathanger’

Sydney Harbour Bridge has become such an iconic Aussie sight that’s it’s hard to believe that it has only been around since the early 1930s.

In fact I find it hard to believe that when Grandma J travelled to Sydney in 1913 the harbour didn’t have either the famous Harbour Bridge or the other Sydney icon – the Sydney Opera House!

The Sydney Harbour Bridge is actually the largest steel arch bridge in the world and is a sight to behold, especially on New Year’s Eve when the pyrotechnics light it up beautifully as it’s broadcast around Australia to bring in yet another new year.

It’s hard to imagine Sydney without the Harbour Bridge as it seems an almost essential artery in the Sydney transport system feeding both into and out of the city, but it wasn’t all easy sailing to get the famous harbour bridge constructed. There were quite a few shenanigans involved in the 10 years between 1922 when tenders for designs were called for and 1932 when the bridge was finally opened.

Milson's Point in 1913 before the Sydney Harbour Bridge was designed or work had even begun. Little could the people in this postcard realize that where they were walking would one day be home to one side of an enormous steel bridge that would ferry Sydneysiders across the river daily.

Sydney Harbour Bridge History

Ideas for a bridge to join the north and south side of Sydney Harbour were first put forward way back in 1815, but the technology that would be involved made the project not just difficult, but extremely expensive. Consequently we entered the 20th century with the idea of a bridge as well just a pipedream.

During the 1800s however steel began to be mass produced and this would change the history of bridge building. As the steel industry was surging forward it was also being used to change the history of bridge building.

One of the pioneers of steel bridges was the German born American John A Roebling who pioneered the use of ‘steel rope’ to make suspension bridges. Essentially he used thick cables of steel intertwined together to form an incredibly strong ‘rope’ that was able to suspend the road part of the bridge between the support pylons.

This idea along with the great improvements that had also been made in the history of welding both helped to inspired people such as Dr John Bradford to continue to dream about a harbour bridge for Sydney and to push towards making that dream a reality.

In 1900 submissions were officially sort for a proposed harbour bridge, but still Sydney would be left relying on a ferry service as all of the submissions were deemed to be unsatisfactory by the New South Wales (NSW) government.

Next in 1923 submissions were called to build a bridge once again, this time the bridge would become a reality.

Between 1900 and 1923 something else that was to inspire the idea of a harbour bridge happened and it’s name was The Hell Gate Bridge. New York’s Hell Gate Bridge was completed in 1916 and it’s design was what is referred to as a through arch bridge. According to Wikipedia the definition of a through arch bridge is “ a bridge made from materials such as steel or reinforced concrete in which an arch rises above the deck so it passes through the arch. Cables in tension suspend the deck from the arch.”

This was the perfect type of bridge to build in order to cross Sydney Harbour as it just wasn’t a solution to support the bridge from beneath during the construction and so inspiration for the resulting Sydney Harbour Bridge had been successfully completed. The planets were aligning and the bridge was about to be born.

In 1922 the NSW government passed the Sydney Harbour Bridge Act and tenders were called for the construction of a bridge between Millers Point in The Rocks and Milsons Point in the North Shore. In 1924 the tender was awarded to an English firm called Dorman Long and Co Ltd. In order to placate Austalian’s about the tender going to an overseas firm assurances were made that the workforce needed to build the bridge would be Australians. In fact over 2000 Australians were employed to build the bridge.

The bridge journey was about to begin and the face of Sydney was going to be changed forever.

The Building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge

Let the Shenanigans Begin!

The actual building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge began in 1923 when the ‘turning of the first sod’ ceremony took place on the north shore on July 28th. The 1920s was a time of prosperity in Australia and on the basis of this the Premier of NSW, Jack Lang, borrowed heavily to finance the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (he also introduced a number of other monetary reforms at the same time). The money borrowed would become the cause of some drama before the bridge was to be completed.

The building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge is credited to a partnership between two men who both shared a dream of wanting to create a bridge to unite the North Shore of Sydney with the bustle of Circular Quay. The two men were Dr John Bradfield, an engineer with the Public Works Department and Jack Lang, the premier of New South Wales.

Jack Lang was a member of the Labour Party and had set up a number of great things such as abolitioning fees for state high schools and setting up pensions for widows. He saw the Harbour Bridge as not just a great piece of infrastructure for the city, but also a source of employment.

In fact the bridge earned a nickname of the Iron Lung because it helped to breathe life into the city by employing many residents during the depression. In fact during the construction of the bridge there were 1400 people working at any given time on the bridge. This also meant that their wages also went into the local community.

John Bradfield was one of the main proponents for the bridge and had been pushing for the building of one to take place since before the first World War. He had recommended first a suspension bridge, then a cantilever bridge before proposing that the bridge should be a steel arch bridge. His vision was a lot grander than just the Sydney Harbour Bridge, however as his grand vision saw the bridge as an extension of a electric suburban railway network.

In the words of Jack Lang “Bradfield wanted to be the Napoleon III of Sydney. He wanted to pull down everything in the way of his grandiose schemes. He was always thinking of the future. He was probably the first man to plan for Sydney as a city of two million.”

So what was with the Shenanigans? Well there was drama and controversy surrounding both of these main movers and shakers in the Bridge build. In John Bradfield’s corner there was a designing controversy whereas Jack Lang’s corner saw a financial scandal erupt.

Most schoolchildren will tell you that JJC Bradfield designed the Sydney Harbour Bridge and this is where the drama about who designed the bridge is all about. Dr Bradfield was the chief engineer of the Sydney Harbour Bridge construction and was the one that pushed for the ‘style of bridge’ that we eventually got. However the detailed design of the bridge that won the tender was created by Ralph Freeman who was a consulting engineer for the company Dorman, Long & Co Ltd who won the tender.

Somewhere along the way the history of the Sydney Harbour Bridge was rewritten to the point that many believe Bradfield had designed it in fact Freeman is reported to have become very upset with Bradfield over comments that he made during construction essentially taking credit for the bridge design himself.

In 1929 the stock markets crashed and the carefree Jazz Age of the 20s was brought to a screeching halt – we were about to enter the depression and yet the NSW government owed a lot of money to Britain including the loan taken out to commission the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. What to do? Well Jack Lang had a plan – re-negotiate a better interest rate with the British banks, unfortunately the other members of the federal Labour Party disagreed and because the federal government had underwritten the NSW government loan they insisted that the payments be made.

Jack Lang refused to stop paying pensions to widows and other such programs that would adversely affect the people of Sydney in order to pay what he saw as crippling interest rates so he instructed his government not to make any loan repayments until Britain re-negotiated interest rates on the money owed. The first loan repayment was then made by the federal government who didn’t want to be seen in a bad light by the ‘mother country.’ The second loan repayment caused all kinds of drama.

Now the official story goes that Jack Lang refused to pay and the upshot was that he was relieved of his position by the Governor of NSW Sir Philip Game. However I recall watching a program on the History Channel that seemed to indicate that he did more than refuse to pay he emptied the government bank accounts and hid the money when a federal government official came to demand payment – it certainly makes for a juicier story!

Sydney Harbour Bridge Trivia

- In 1932, before the bridge was opened 96 steam locomotives were positioned in various different ways to test it’s load capacity.

- Officially opened on 19th March 1932.

- 800 families were relocated when their homes were destoyed in order to build the bridge.

- During construction of the bridge 53,000 tonnes of steel was used along with 6 million hand driven rivets.

- 16 workmen died during the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

- When the harbour bridge is painted it uses approx. 80,000 liters of paint for just one coat.

- Today more than 150,000 vehicles cross the bridge daily.

You might also like

Sydney, Australia: History and HeritageFacing the South Pacific Ocean, Sydney is Australia's largest city. It is fam...

Blue Mountains, AustraliaThe beautiful Blue Mountains are a little to the west of Sydney, NSW, Austral...

One Direction Gift Ideason 11/13/2012

One Direction Gift Ideason 11/13/2012

One Direction Christmas Ornamentson 10/23/2012

One Direction Christmas Ornamentson 10/23/2012

How to Create a Dora the Explorer Bedroomon 08/01/2012

How to Create a Dora the Explorer Bedroomon 08/01/2012

How to Create a Sleeping Beauty Bedroomon 08/02/2012

How to Create a Sleeping Beauty Bedroomon 08/02/2012

Comments

Jack Lang was a larger than life figure who is still admired by many in New South Wales. He had his faults but he tried to help people who were doing it tough during the Great Depression.