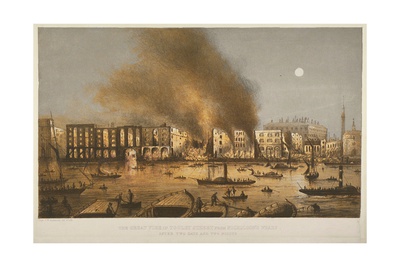

Who would have thought that there would or could be another Great Fire in London? Well there was, almost two hundred years after the first, but on the other side of the river, in sight of the start of the first one, this with a very different cause. Whilst the Great Fire started in a bakery, the Tooley Street fire started in a warehouse not far from London Bridge. It took two weeks to extinguish and caused damage estimated to be £2m.

The Biggest Fire Since the Great Fire of London

by Telesto

What? Another great fire in London? Yes, and it took two weeks to extinguish this one. It happened in sight of the start of the 1666 fire, on the other side of the river.

The Tooley Street fire is the biggest London fire since the Great Fire of London occurred in 1666.

Tooley Street runs almost parallel to the south bank of the Thames, running east from London Bridge. Today, it’s full of bars, restaurants and up market shops, but in the 19th century, it was full of warehouses, wharfs and other places for storing imported goods brought up the river. In those days, it was part of the pool of London, still very much associated with London’s river trade.

The Tooley Street fire started in one such warehouse at Cotton’s Wharf in the afternoon of Saturday, 22 June 1861, in full sight of where the 1666 fire started. The warehouse was full of the usual array of imported goods such as cotton, jute, hemp, various spices, bacon, tea, coffee and so on.

Unfortunately, the fire spread far more quickly than it should have; the fire doors that should have separated the storage rooms had been left open. It is highly probable that the fire might have burnt out, or at least, caused far less damage had they been closed.

The alarm was sounded at about 4pm when someone saw smoke coming out of the building. In those days, there was no London Fire Brigade, but there was a London Fire Engine Establishment, established by a group of insurance companies, and they attended to fight the fire.

As is often the case, one mistake was compounded by another, and there was a lack of water supply, even though the warehouse was close to the Thames. It was low tide and there was no water supply forthcoming for nearly an hour after the start of the fire.

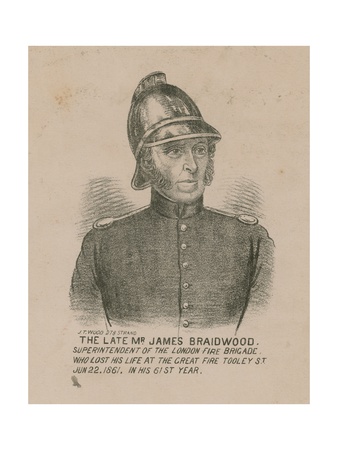

By six o’clock that evening, there were 14 fire engines in attendance, including a steam fire engine and a floating engine. James Braidwood, Superintendent of the London Fire Engine Establishment, saw that the fire fighters were becoming tired and ordered that they all receive a nip of brandy!

Braidwood had been a surveyor prior to becoming a fire fighter, and the methods he introduced, including knowledge of building construction, are still used today. Sadly, Braidwood, who was superintendent for 28 years, died in the fire. He was helping one of the fire fighters when a section of warehouse collapsed on top of him. He is believed to have been killed instantly, although it was three days before his body was recovered because of the intensity of the fire.

By late evening, the fire was seemingly out of control - it is said to have spread as far down the river as Custom House, not the place of that name that still exists on the north side, opposite the Greenwich peninsula, but the Rotherhithe one, a few miles along the south side of the river. The fire was so hot that it was impossible to direct enough water on it to control it. Before long, fire engines from all over the country had arrived to assist in controlling the fire.

The fire drew a crowd of over 30,000 people from all over London. The pubs stayed open all day and all night (yes, it was against the law) and anyone who sold drinks and other refreshments did a roaring trade. Reports from the time say that London Bridge itself was packed with thousands of bystanders, and that the fire could be seen as far away as Epsom, in Surrey, some 18 miles south.

It took two weeks to put out the blaze - far longer than the three days it took for the Great Fire of London. Offices, sail boats, barges, even an American Steamer were destroyed as well as 20 warehouses containing 5,000 tons of rice, 10,000 barrels of tallow, 1,000 tons of hemp, 3,000 tons of sugar, 18,000 bales of cotton and more. The cost was estimated at £2m. In contrast, the fire engines, fire pumps and volunteers’ costs are estimated at £1,100.

They say every cloud has a silver lining, and in this case, the insurance companies and the people of London all got some benefit. The insurance companies inevitably increased their premiums and insisted on improvements in the storage of goods in warehouses. They also wrote to the Home Secretary a few months later and told him that they could no longer be responsible for London’s fire safety. In 1865, the Metropolitan Fire Brigade Act was passed, and from 1 January 1866, the Metropolitan Fire Brigade commenced service.

You might also like

Myths Uncovered about Southern StereotypesHollywood, politics, the media, and others choose to paint Southerners as dum...

Newly Single, Now What?Newly single and struggling? Things you can do to ease the transition from be...

Celebrating ChristmasThe Christmas celebrations have layers of history in them accumulated over ce...

Identity Theft and How it Feelson 02/01/2015

Identity Theft and How it Feelson 02/01/2015

Barts Hospital - a National Treasureon 01/24/2015

Barts Hospital - a National Treasureon 01/24/2015

Urban Foxeson 01/11/2015

Urban Foxeson 01/11/2015

How do you know which hosting platform to choose?on 01/03/2015

How do you know which hosting platform to choose?on 01/03/2015

Comments

Thank you Ologsinquito. To be honest, I hadn't heard of it either. I was researching something else and came across it, and was fascinated because I know the area. I guess it's the same for us though, we only hear about the big things over there. Happy New Year!

Very nice article. I've never heard of this fire. Then again, we don't hear about a lot that happens on the other side of the Atlantic.