Gwyn

Handsome my dog, and round-bodied,

And truly the best of dogs; Dormarth was he, which belonged to Maelgwyn.

Gwyddno

Dormarth with the ruddy nose! what a gazer

Thou art upon me because I notice Thy wanderings on Gwibir Vynyd...

Which is quite a curious statement, because why would a real life 6th century chieftain not only present a British God with a dog (unless it was a sacrifice), but that particular hound?

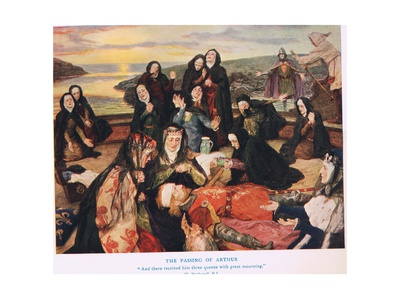

It also seems quite awkwardly placed. In the lines leading into it, the dialogue is all about a terrible battle at Caer Vandwy (God's Peak Fortress), wherein few survived. Gwyn ap Nudd witnessed it all, as he was there in his official capacity as God of the Underworld. (This battle is also mentioned in the Arthurian legend The Spoils of Annwn, where we're told only seven survived amidst both armies.)

So it's 'blah, blah, lots of dead British people, blah, blah, battle - oh! By the way, do you like the lovely dog that Maelgwn Gwynedd gave me? Dormarth's the leader of my pack of Cwn Annwn, you know!' At least that's how it reads to me.

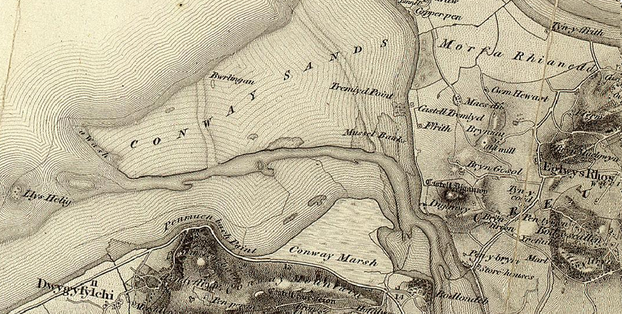

Gwyddno - the 6th century chieftain of a flooded region, which was said to have been located where Cardigan Bay now lies - agrees that the dog is very nice, and comments that he's seen Dormarth running around Gwibir Vynyd (Mountain in the Clouds). Then the conversation promptly switches to the Battle of Arfderydd.

This was a real world clash, dated to circa 573 CE, wherein two chieftains of the Old North slogged it out for sovereignty over a region stretching from Lancashire to Strathclyde, i.e. nowhere near Gwynedd. Though I have recently read at least two attempts to relocate it there, and one which reworked the dates from the Annals Cambraie in order to have Maelgwn fighting at Arfderydd, despite historians generally agreeing that he died nearly thirty years before.

However, one aspect might be relevant. Arfderydd is mostly famous for being the battle after which Merlin went mad. But It's also a renowned clash between a Pagan and a Christian chieftain, seen as one of the earliest such which may have had as much to do with religion as territorial gains.

It's the Pagan leader Gwenddoleu whom Gwyn ap Nudd mentions in the poem, after they've finished talking about Maelgwn's gift of an otherworldly dog. A link is implied, if not directly stated, between Gwenddoleu and Maelgwn.

However, I'd read it all much more specifically than that. To my mind, Gwyn ap Nudd is saying that Maelgwn's gift is to provide protection for the spiritual realm. The fact that the symbolism is a dog could be a play on Maelgwn's own name - Princely Hound, or Warrior Hound - or else could invoke the notion of a guard-dog. Both work and both were probably intended.

And the necessity for Maelgwn's role comes in the fact that Britons are battling Christians and invaders. Unless I'm reading too much into it.

(Another avenue of investigation may be the fact that St Kentigern (trans. Hound Chieftain), aka St Mungo, the legendary founder of Glasgow, was also said to have been at the battle of Arfderydd. The stories attached to him often run so parallel to those told about Maelgwn, that some are downright identical.)

The fact that it's Gwyddno speaking here could also be significant. Melkin's Prophecy states that Britons will never want for water (Britannia will indeed rule the waves). Gwyddno's lands were flooded into oblivion. However water was very sacred to the ancient Cymry. Wells, lakes and rivers tended to be populated with their own deities, and provided access to the spiritual realms. 'Water' could very easily be a metaphor for the Druidic religion.

Moreover, Gwyddno is generally viewed as the (adopted) grandfather of Taliesin. The Welsh Bardic tradition did more than anything else to preserve the legends and histories of the Old Religion, and Taliesin was its undoubted champion.

And he too had a significant series of encounters with Maelgwn Gwynedd.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Yes, I can see that being an accurate etymology.

Thanks for that. I thought that that might be the case, but I do not know enough Welsh to be sure. Prichard probably was ap Richard, which is a Welsh-Norman cross.

Frank - ap means 'son of', so exactly like 'Fitz' insofar as it's offspring, but not necessarily illegitimate. 'ap' was the norm (for males), with 'merch' or 'ferch' being the female equivalent.

Peter - You're into patronymics. That was the Welsh way of rendering names, before the introduction of English style surnames in the 18th and 19th centuries. Some went on until the 20th.

The Welsh and Norman aristocracy happily collaborated when it suited them, as they did in the first Norman invasion of Ireland. Interbreeding was therefore likely among these cronies. Hence ap might be a prefix similar to the Irish fitz, which indicates the illegitimate son of a noble, rather than one of their serfs/servants.

We have to be aware that aristocrats have been known to co-operate with invaders to keep their land, and the invaders often see them as useful allies. The Saxon thanes went along with William, though it did not help them in the long term.

I've been digging in to find out anything I can about Mortimer's Cross - how it got its name (beyond what seems obvious) in particular. But you're right. There is a distinct lack of information in the historical record.

I'm quite used to blanks, given the number of times that Welsh and Marches documentation has been destroyed over the years. But this one appears Norman related, hence you'd have expected some survival. Unless it's old Henry Tudor to blame again.

And yes, re what Frank wrote regarding what happens to names under Occupations. It happens across the board - look at Romanisations under the Roman Occupation etc. Plus you have another factor, which is older names appearing in their Latin form, when it's only ever monks recording them.

Strata Florida keeps coming up again and again and again just recently. I think I'm going to take a deeper look there. This isn't just with regard to the Mortimers either. Until you mentioned it, I had no idea of their involvement.

You do have me thinking through. Have you ever heard of anything involving the Mortimers and the Arthurian legend? Call it a hunch.

One factor to be considered is that certain non-Normans normanized their names to gain status. For example, the Fitzpatrick clan in Ireland sound Norman, but in fact they were an Irish clan who decided to sound classier, so they ditched the Gaelic name and took a Norman one. Note how old Saxon forenames fell out of use after the Norman conquest.

I agree that the name Mortimer's Cross precedes the battle, as battles take their names from existing landmarks.

Indeed. Gwynne Williams says that "Welshmen became citizens, merchants, and knights" under the Normans, and mentions Mortimer having some involvement with Strata Florida - so they were not just concerned with the Marches, but also deepest Ceredigion.

Extremely anachronistic. Have you read 'When Was Wales?' A great run through of that.