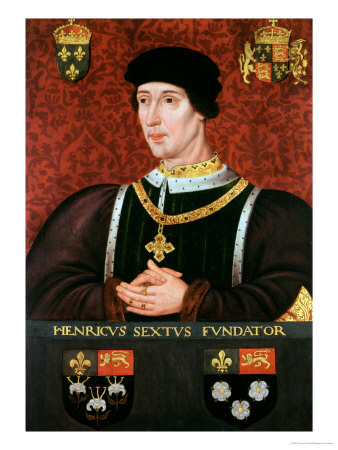

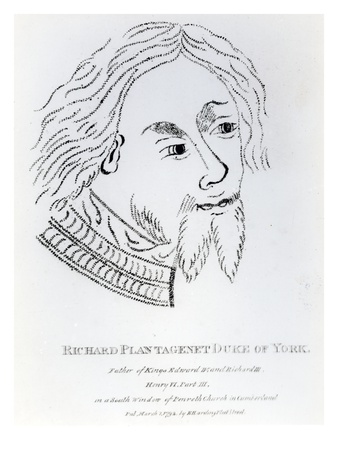

For the next three years, it seemed that the uneasy peace might just about hold. Richard, Duke of York, was sent over the Irish Sea to become the Lieutenant of Ireland.

With him safely out of the way, Henry and Margaret could systematically dismantle all that he'd put into place during his regency. His supporters maintained a few small skirmishes, mostly inside the city of London. But none of them appeared about to erupt into actual armed conflict.

But no-one was watching Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. When he began acting without due regard to his sovereign, then action had to be taken. Henry VI was persuaded by his wife to summon all of the York faction to a court in Coventry. They would be dealt with together.

Except they didn't turn up.

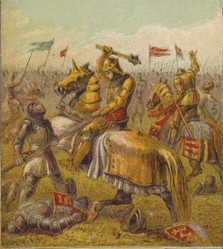

Sensing trouble, the York forces led by the Earl of Salisbury left Middleham Castle in Yorkshire, aiming to meet up with a huge York army gathering in Ludlow Castle in Shropshire. Margaret of Anjou ordered Lord Audley to intercept them and that clash occurred at Blore Heath in Staffordshire.

It's amazing how many times Medieval battles were decided by a stream in the middle of the battlefield. Horses and infantry alike do tend to get bogged down in the mud and water.

On the morning of September 23rd 1459, that's precisely what happened here. Lord Audley knew about the brook. He'd positioned his 10,000 strong Lancastrian army to make good use of it. The idea being that the York men would be forced to cross the boggy patch, where they would be sitting ducks for the Lancastrians firing arrows at them.

However, that's just one angle of a battle-site. For the Earl of Salisbury, turning up with 5,000 men and realizing he was outnumbered, it was quite imperative to have a good look at the terrain. He noticed the brook; he discerned the plan.

Turning those tactics 180 degrees, Salisbury ordered his whole middle section to suddenly retreat. Sensing a rout, the Lancastrians surged forward, straight across the stream.

Where they became bogged down and were sitting ducks, when the York forces immediately came back and started firing on them. It's said that Lord Audley never gave the order to charge, but he was killed anyway.

It was a very decisive York victory on that morning in Staffordshire. Two thousand Lancastrians lost their lives to prove it.

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

St Tydecho's Churches in West Waleson 09/03/2014

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Goodies for an Outlander Premiere Partyon 03/06/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Holocaust Memorial Day Interview with Rainer Höss, Grandson of Rudolf Architect of Auschwitzon 01/24/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Romantic Valentine Gifts for an Outlander Fanon 01/16/2015

Comments

Thank you very much! There are some parts of history that I can't touch either, because I couldn't be impartial, like the Miners' Strike.

Great telling of the first part. Bang from 'Yorkshire I've always been on Yorks' side. I don't think I could have created something impartial so I'm really glad you have. This was the first part of history that I loved and still can't get enough of it.

You originally had ours! Then went and kicked us out in the American War of Independence. Poor tea... *mourns in memory of Boston Harbour*

Reading this reminds me that there are big cultural differences between American and Britain. We've never had a monarchy. Great article.

I'm very pleased to hear it! History is fascinating, if it's not butchered by teachers.

Great job recounting this history. I remember hating my history studies in school, who could care which Richard or Henry became king next and which years did they reign.... But you make it much more interesting!