Alfred Ely Beach and his secret subway.

by wcascade40

There wasn't a legal way for Beach to build his NYC subway so he built it in secret.

In 1912 a construction crew under the city of New York was digging a new subway tunnel, when suddenly they broke through into an unknown tunnel. The tunnel contained an elegant station and a small train and tracks.

The workers were startled, but they had uncovered the remains of Alfred Ely Beach’s attempt to build a subway in the 1870’s. He tried to build it in defiance of the corrupt state administration and powerful business interests, but he ultimately lost and the tunnel was boarded up and forgotten.

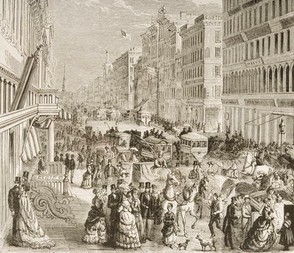

New York City had a population of about 700,000 by the end of the Civil War. Immigrants were streaming into the city and the city was rapidly expanding. Public transportation was not adequate. The streets were not that wide and the large horse drawn streetcars and omnibuses were clogging the streets. There were huge traffic jams and the streets were actually louder than they are today. Something needed to be done.

BEACH'S PLAN |

Alfred Ely Beach was a successful patent attorney, publisher and inventor. Among other things, he invented, the first practical typewriter, a pneumatic tube and a hydraulic tunneling bore, which he used in the construction of his subway. It was later used to construct both the New York and London subway systems.

Beach also invented a typewriter that could be used to print Braille characters. Beach also published the Scientific American for a time before going on to publish the New York Sun. He was successful at both publications but by the age of 26, he had made both successful and was looking for new challenges. He turned to patent law, defending the patents of hundreds of his fellow inventors, including Thomas Edison, Samuel F. B. Morse and Elias Howe.

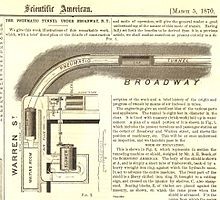

When Beach was only 23, in 1849, he first thought of a subway. His idea was a tunnel under Broadway and he expanded his idea in Scientific American. The subway would have “openings at every corner. There would be 2 tracks, with a footpath running between them, the whole to be brilliantly lighted with gas. The cars, to be drawn by horses, would stop 10 seconds at every corner.”

Beach kept pushing his idea at both publications but nothing came of it. In 1866 he began to experiment with pneumatic power to move his subway. There was as yet no electrical or gasoline engines, so the only other alternative was steam engines. Beach was sure that people would not want to be in a tunnel with a dirty engine that could explode at any moment. Pneumatic power was the only way, but was it possible?

In 1867 at the American Institute Fair in New York he tried to give a practical demonstration. He built a wooden tube 6 feet in diameter with a car that could carry 10 passengers. A helix fan, larger than the tube, pushed air into the 6 foot pipe and blew customers from 14th street to 15th street then reversed and back again. The exhibit was very popular and had hundreds of passengers.

Beach now had renewed determination to build his subway. But he did not want to get involved in the political wrangling necessary to get approval. He was not the first man to ask the legislature for permission to build a subway, but he wanted to be the first man to actually make one.

So he asked for approval of a underground pneumatic mail system. The (fake) purpose of the tubes was to whisk the mail from where it was deposited in a hollow lamp post along tunnels to a distribution station. There they would be gathered together and sent on their way very speedily and efficiently. The plan seemed harmless enough and Boss Tweed approved it. Tweed was the corrupt head of Tammany Hall that had a grip on city and state politics, swindling and taking bribes.

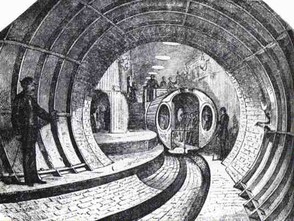

Alfred Ely Beach designed the railway in secret and had it built, over 58 successive nights, without anyone noticing. The tunnel started in the basement of Devlin’s Clothing Store. Beach’s son Fred supervised the workers. The dirt was hauled away in wagons with wheels muffled to remain silent. These same wagons brought in needed supplies. There was no evidence on the surface for a casual observer to see.

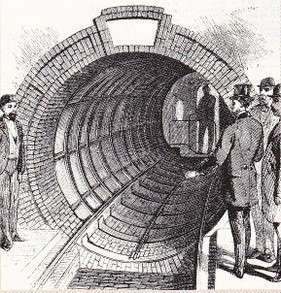

The subway consisted of a cylindrical tunnel 9 feet in diameter with a track laid on the bottom. The tunnel was over 300 feet below Broadway. The cars was snugly fit into the tunnel. The Roots Patent Force Blast Blower pushed the car down the tracks at about 10 MPH. Once the car reached the end of the track, a wire was tripped and the Blower automatically reversed to send the car back to the first station.

The subway was no crude affair. The waiting room had frescoed walls covered with paintings, a grand piano, fountain and fish tank. There was one small elegantly upholstered car that seated 22 passengers. Beech also used zircon lights in his large waiting room, to make customers more comfortable.

In February, 1870, Beach gave an announcement to the newspapers about his secret subway and invited reporters and guests to try out his invention. He had been able to keep it a complete secret. Boss Tweed and the other politicians were absolutely furious at the trick. But New Yorkers loved it, within the next year over 400,000 people had come to view and ride on the formerly secret railway.

Once reporters had toured the subway their reaction was delight. The Scientific American stated “This means the end of street dust of which uptown residents get not only their fill, but more than their fill, so that it runs over and collects on their hair, their beards, their eyebrows and floats in their dress like the vapor of a frosty morning. Such discomforts will never be found in the tunnel!” Beach did own the newspaper so maybe you should take this with a grain of salt but the subway was quite popular.

derelict car |

One group who didn’t like it however were the owners of the Broadway properties above the subway, who thought the tunnel had the potential to destroy their buildings. The politicians weren’t thrilled either. Tweed had approved it so his enemies wanted nothing to do with it. Tweed wasn’t going to fight for it, he wasn’t going to make any money out of it. So the subway was a political orphan.

It was a popular tourist attraction but not practical public transportation ,it would have the be vastly expanded and the government would not allow this. But eventually, after much work by Beach, a bill passed in the New York legislature , in 1873, approving the railway. By this time, Beach was tried from the fight and had no money to build a longer subway. Beach was dispirited by the matter and never invented again. He turned to publishing and became more religious and even more charitable. He eventually founded a school for freed slaves and was active in many charities.

New York City turned to Elevated Railways ,which were considered more practical, before the city finally got subways, starting in 1904. Today all that remains of the station and 312 feet of track is a plaque on the City Hall subway station and Beach, who died in 1896, is forgotten. But in a way, he is the father of the American subway and deserves to be remembered.

books on New York City

|  |  |

| New York: An Illustrated History (Rev... | Taking Manhattan: The Extraordinary E... | The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910 |

You might also like

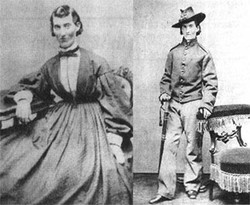

The Women Who Fought in the American Civil WarWhen we imagine the heat and blood of Gettysburg, it's the men that we see st...

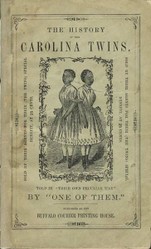

The Carolina Conjoined Slave Twins Born in 1851In 1851 children who were born ill or with special needs seldom survived. Con...

Invention of Breakfast Cerealon 08/24/2011

Invention of Breakfast Cerealon 08/24/2011

Sniglets Words that don't appear in a Dictionary but should.on 08/24/2011

Sniglets Words that don't appear in a Dictionary but should.on 08/24/2011

Halloween romantic superstitionon 08/23/2011

Halloween romantic superstitionon 08/23/2011

Safety Bicycle sparks cycling craze in USon 08/23/2011

Safety Bicycle sparks cycling craze in USon 08/23/2011

Comments