Bare knuckle boxing was illegal in Britain but the early 19th century newspapers reported matches in lurid detail.. Victors were regarded as heroes - during the Napoleonic Wars young Jem Belcher was more famous than Napoleon or Wellington. Lords, Dukes and even royalty paraded their chosen champions but as soon as they lost many faced a grim future of disappointment, poverty and gin.

Bare Knuckle Boxing in the Early 19th Century

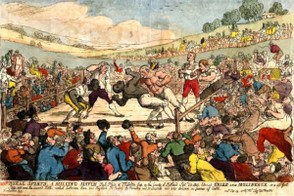

Prizefighting was one of the few places where rich and poor rubbed shoulders. The rich sometimes lost a fortune, the poor often lost their lives.

From the Coliseum to Gin Lane

Prizefighting in Britain

In the time between Napoleon 1 declaring himself Emperor of France and Queen Victoria ascending the throne of England, the moneyed classes were swept along by gambling mania. Nights at the gaming table followed days at the races but the greatest rise in aristocratic entertainment, was the prize ring.

In the time between Napoleon 1 declaring himself Emperor of France and Queen Victoria ascending the throne of England, the moneyed classes were swept along by gambling mania. Nights at the gaming table followed days at the races but the greatest rise in aristocratic entertainment, was the prize ring.

The Sport of Kings?

Bare-knuckle boxing was open to anyone willing to step up to the line. It was the rich, however, who called the shots, putting up the prize money, patronising some young hopeful with the makings of a good fighter. After a drunken, sporting dinner at the Franklin, when the guests got around to discussing the merits of certain fighters, “a noble lord“ proposed a match between two pugilists Randall and Martin and the challenge was accepted by Martin’s friends. The Manchester Mercury of May 13 1817 went on to comment that the prime Irish lad had nothing to do personally in making the match; but the courage of Randall would not let him refuse it when asked by his Lordship. The boxers were often pawns in a rich man’s game.

What the Papers Said

In much the same way that horseracing and football is covered in the modern press, so details of forthcoming boxing matches and blow by blow accounts of fights featured in the newspapers. Early 19th century pundits pontificated on the merits of potential challengers and forecast the likely outcome.

Bare-knuckle boxing was illegal in England, not least because a gathering of the ‘great unwashed’ invariably resulted in disorder. The Riot Act of 1714 proved a useful tool to forestall trouble and as a result, the venue for such events was kept secret until the last minute. Forthcoming matches were often advertised as “within fifteen miles of London,” or “within twelve miles of Southampton.” Those in the know could guess the likely spot.

A Dangerous Game

Opportunities for poor, working men to grow rich were rare indeed, but if you were handy with your fists and could take the punishment, then there was a chance of both wealth and adulation, two potent drugs. They came, however, at a cost. With depressing frequency, the thrill of success and the magic of gold in your pocket degenerated into a loss of status, heavy drinking, gambling, damage to health and an early death. Jack Randall, mentioned above, was a case in point.

Jack Randall was born in London on November 25 1794, the son of poor Irish parents. By the age of 13 he was earning a few coins with his fists. In 16 recorded fights, he won 15 by knocking out his opponents, earning the sobriquet Non Pareil. His exploits became so celebrated that he even appeared on the stage of the Regency Theatre, acting out his triumphs.

To safeguard his future, Jack invested in bricks and mortar and acquired the Hole in the Wall pub in Chancery Lane that soon became a Mecca for boxing aficionados.

The critic William Hazlitt recorded calling at the Hole in the Wall to ascertain the venue for a forthcoming fight between “Neate the Butcher, and Hickman the Gas Man.”. He did so with some trepidation, having been previously ejected with “unnecessary force,” by mine host, after having made some minor comment about a chop.

At his hostelry Jack entertained a liberal clientele, always happy to ply him with drinks and tellingly, by October 1827, when pushed to accept a boxing challenge, he declined.

The Morning Post of October 15 issued a statement from the boxer saying: “It must be well known that my condition cannot be much improving, from my occupation as a publican.” Indeed, within the year, Jack died of an alcohol-related illness. He was 33.

Simon Byrne and James “Deaf” Burke.

An unfortunate chain of events linked these two would-be champions. Byrne “The Emerald Gem” was born in 1806 in Ireland and having won the championship of that country he came to England in search of bigger prizes. On June 2, 1830 he took on the Scottish champion Alexander McKay at Hanshope in Buckinghamshire. The match aroused huge interest and the “Fancy”(boxing enthusiasts) was there in force. After 47 rounds, a blow across the throat saw McKay collapse. The following evening June 3rd he died. He was 25 years old.

The Chester Chronicle followed the case, reporting that poor Mckay’s face “was so frightfully cut and disfigured, that the features were lost in a confused mass of gore and bruises.” A post mortem revealed damage to the brain and Byrne and the four accompanying seconds and bottle holders were jointly charged with manslaughter. At the trial however, influential forces came to their rescue and an impressive array of barristers and solicitors offered a defence. As a result all five men were found not guilty The Chester Chronicle (June 11 1830) railed against these …wealthy monsters in this affair of blood… the sanguinary cowards who stood by and saw a fellow creature beaten to death for their sport and gain!”

On May 31, 1833, Byrne faced James Burke, contending for the Championship of England. Burke was born on December 18 1809, and worked as a Thames water-man rowing passengers across the river. During his career he became known for his gruelling marathon boxing matches and early on, one bout lasted so long that it had to be stopped because it was too dark to see.

Burke and Byrne now embarked upon a vicious fight that lasted for 99 rounds. During this time Burke’s ear was bitten through. At one point he was said to have collapsed vomiting blood, but the fight continued for over three hours and it was Byrne who finally fell down unconscious. Three days later he died. He was 37 years old.

Burke was tried for his murder, but a post mortem suggested that the Irishman might have had an existing condition of the lungs so Burke was acquitted.

Thereafter, potential champions were wary of fighting him so that he tried his luck in America then France and on returning to England survived by giving boxing lessons. By this time, that 19th century scourge of TB claimed him. In an obituary in the Kendal Mercury January 18 1845, it was observed that during his career he had earned “considerable amounts of money, of which, at his death, there remained, unfortunately, a very small remnant, if any.” He was described as very generous, the “Hero of twenty fights,” and on one occasion he had rescued horses at Astley’s when a fire raged at its fiercest, proving that “true courage is ever allied with humanity.” He had died ten days earlier, aged 36

Jem Belcher and Henry “Game Chicken” Pearce.

Tragedy also linked these two boxing stars, their lights being extinguished far too young.

Jem Belcher, the son of a butcher was born on 15 April 1781 and came from a boxing family. His maternal grandfather, James Figg was the first official Champion of England and was said to have won 269 out of 270 fights.

In 1800 Jem too claimed the championship. Elegant, fast, he was the darling of the aristocracy, mixing in their company, enjoying the good life, then at the age of 22, tragedy struck. Playing Fives, he was hit in the face and blinded in one eye, thus ending his high-flying career.

Following a familiar route for retired boxers, he acquired a pub, the Jolly Brewer in Soho and for a while found consolation by promoting other promising fighters. Among them, was a young Bristolian, Henry “Hen” Pearce and before long Pearce began to claim the limelight. Watching his protégé eclipse him, Belcher’s envy drove him to challenge Pearce to a match. Pearce felt that he had no choice but to agree and in 18 heartbreaking rounds, Belcher was decisively thrashed. He tried a second time to claw back some of his success, against champion Tom Cribb, but again he was beaten. Now thoroughly demoralised, he sank into a round of depression and drinking. On July 30 1811 he succumbed to pneumonia and died, aged only 30. The Morning Chronicle of the 31st reported his death at his house, the Coach and Horses in Frith Street, “after a lingering illness of two years which reduced him to a mere skeleton.” His funeral was attended by upwards of 10,000 people.

Henry Pearce came young to boxing and was reputed to the have won all his early matches, but it was when Jem Belcher brought him to London that his career really took off. Between 1803 and 1805 he fought seven bloody contests, gaining the Championship of England. In his fight against Jack Fearby, it was feared that the latter was dead, although he ultimately recovered, while in a championship fight lasting 64 rounds against John Gully, Gully was struck across the throat and stopped breathing. It was the match against his patron and hero Belcher however that proved to be his last.

The experience of humiliating his friend and sponsor virtually ended his career.

Over the next two years he continued to give exhibition matches. Once he rescued a young woman from a burning building while on another occasion he was said to have trounced three men who were attacking a girl. By this time however, his health was suffering and he had developed tuberculosis. Boxing was still in his blood and in spite of the icy weather, on February 1st 1809 he hastened to watch the fight between Jem Belcher and Tom Cribb. Now desperately ill, Hen Pearce lingered for a few more weeks, dying in London on April 30 1809. The Morning Post of May 2 announced that “his pugilistic career was put to an end by a complaint of the lungs, brought on by dissipated habits, and which at length caused his dissolution.” He was aged 32.

Outsiders

The labouring class apart, three distinct groups of citizens also saw prize fighting as a chance to improve their lot. They were the Jews, the Romany and the Africans. They faced the same problems as their Anglo-Saxon contemporaries, plus the frequent hurdle of prejudice. Faced with a “foreigner” in the ring, the indigenous English found a focus for their xenophobia although sometimes, if a man proved himself to have plenty of “bottom” he might then become the darling of the boxing cognoscenti. However, they remained a part of, yet apart from the mainstream.

Elias “Dutch Sam” Samuel, “the Jew,” “the Hebrew,” “the son of Israel,” was born in 1776 in Whitechapel. After a successful but punishing number of fights (some say nearly a hundred) Sam retired having suffered only two defeats. In 1814 during a drunken encounter, he accepted a challenge from one William Nosworthy, a baker. His East End supporters, confident of his success, bet heavily on him to win but things went badly wrong and in round 9 his supporters invaded the ring. The Exeter Flying Post (December 16 1814) reported that this disruption was “laid to the charge of the Jews, to save their money and Sam’s credit.” The fight continued but after 40 rounds, “in a fit of despair, Sam yielded the palm of victory to the sturdy baker.” The Post then revealed that Sam was known to “guzzle down ten or a dozen glasses of gin in a morning.” In its obituary, the Chester Chronicle (July 26 1816) confirmed that between his retirement and fighting Nosworthy, “five years had passed in complete dissipation and intemperance…he sank into dejection, misery and want.’ He died in London Hospital on Wednesday July 3 1816, aged 41.

Jack “Gypsy” Cooper came from a Romany family known for fighting. Under the heading Gypsies, an editorial in the Cambridge Chronicle and Journal of July 26 1816 stated that “of late years, some attempts have been made to reduce the numbers, or at any rate to civilize[sec] the habits of that vagabond and useless race…”. It listed the names of gypsy families among which, was Cooper.

Jack’s first official fight came at the age of 20 when for £10 he was matched to Somerset man West Country Dick. According to the Morning Chronicle, May 17, 1820, Dick had been up all night drinking and was lushed heavily but was the favourite. In the ensuing 29 rounds Cooper appeared immune to being hit and slowly wore his opponent out. The Chronicle reported that Dick was “terribly beat,” and had to be taken away.

On August 9 1821, the Morning Post regretted to announce that following the match between Cooper and Irish champion O’Leary two days earlier, the latter had died and that an inquest would take place that morning. The Cambridge Chronicle and Journal covered the story. Witnesses confirmed that it was a fair match. O’Leary had the best of it until an unfortunate blow to his temple ended the contest. Mr Wallace the surgeon opined that O’Leary died from the effects of the match but he hadn’t actually examined the head, at which point the coroner ordered that he should do so. The body “which was in a putrid state, was taken out of the coffin and the head opened.” There was a rupture of the brain but in Dr Wallace’s opinion, not enough blood to have occasioned death. The verdict was nevertheless that the deceased had lost his life whilst engaged in an illegal transaction. Cooper was charged with manslaughter for which he spent several months in gaol.

Jack Cooper was no stranger to the courts. In January 1824 he appeared on a charge of rioting and “cocked his eye at the Chairman in a very knowing manner,”(Sussex Advertiser). In view of the evidence however, he was found not guilty.

By 1823 he seemed to be over the hill and began to lose contests, then some time after 1825 he was transported to Australia for an unspecified crime (www.romanygenes.com). At the end of his sentence he chose to remain there and allegedly died in Tasmania at 105 years of age.

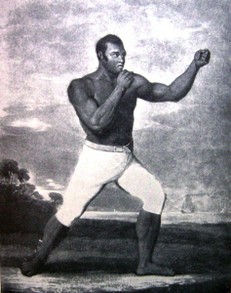

Tom Molineux epitomised the mercurial life of a 19th century black boxer. Born into slavery, his master grew rich from his boxing abilities. Tom was rewarded with his freedom and in 1809 came to England where he fell in with black American Bill Richmond who became his mentor. Richmond ran his own boxing school, approximately where Nelson's Column now stands. His ambition had been thwarted when he failed to beat the boxing champion Tom Cribb and through Molineux he hoped to get his revenge.

After several boxing successes, Molineux discovered the joys of celebrity. He was taken up by the glitterati, both male and female. The Bury and Norwich Post, May 22 1811 announced that Molineux the black pugilist had a dinner party on Thursday, which was graced by two Noble Marquises, 6 lords, 4 baronets, with several Right Honourables, Captains, Esquires, Fighting men, etc.

The battle with Tom Cribb was arranged for October 1811 going down in the annals of boxing lore. However popular Molineux might be in some circles, national pride demanded that the English Cribb should prevail and as soon as he showed signs of losing, the ring was invaded. During this furore, Molineux’s hand was badly damaged. In spite of this the bout continued but after 40 rounds Cribb emerged triumphant.

Having failed to fulfil Richmond’s dreams, Molineux was cast aside. Broke and heavily dependent on drink, he made his way to Ireland. The Chester Chronicle (August 28) reported that thanks to the “humanity and attendance of three men of colour,” Molineux was kept alive until August 4 1818, dying at their army barracks in Galway. The Chronicle expressed the opinion that Tom had been viewed by English boxers “with jealousy, concern and terror”. He was a “fine young man of stamina and strength of the first quality but he did not have a shadow of a chance”.

He was thirty-four.

First Aid

Medical care was cursory. During a match, it was not unknown to lance the swollen tissue around an injured eye so that the boxer could see to continue.

When poor Alexander McKay left the ring, “he was so bruised about the nose as to make that organ useless in the act of respiration”(York Herald June 12 1830). Immediately he was bled on the arm and this having little effect, later bled in the temple. When this failed, his head was shaved and a mustard poultice applied, but he died. When his conqueror Simon Byrne in turn was fatally injured, the surgeon gave evidence that leeches were applied to his bruised head and his right ear was lanced, but to no good effect.

The End of an Era

It cannot be coincidence that with the accession of Queen Victoria, boxing gradually fell from favour. Until that time it had the support of both King George IV and William IV, while the Duke of Cumberland alone, lost £10,000 on a single match.

The Irish Champion Dan Donnelly was pleased to recount his meeting with the Prince Regent: “the finest prince I ever dhrunk wid,” (The Belfast News-letter, September 11 1829). The prince insisted on having a sparring match, during which time Donnelly knocked him down. Un-phased, Prince George then allegedly presented him with a knighthood. At the height of his career Donnelly owned his own carriage with liveried servants, then became a publican. Too soon he earned a reputation as a boozer, gambler and womaniser. He died on Feb 18 1820, aged 32.

The emergence of the new royal family as models of respectability slowly changed the national attitude to fighting. In 1887, looking back on the century, the Hampshire Telegraph wondered at a time when “Champions of the ring were the pets of every class of society and their deeds were as well known then as the deeds of Nelson and they were regarded as little lower on the ladder of heroism.

The 19th publication Boxiana by Pierce Egan gives a vivid contemporary account of 19th century prize fighting. The on-line Boxing Hall of Fame also includes biographies of many of the fighters mentioned in this article.

You might also like

Thinking about NalediThe new discoveries in the Rising Star cave in South Africa arouse questions ...

Shipwreck: the Edmund FitzgeraldBesides the song Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, there's so much more about t...

Snooker Dooperon 04/28/2019

Snooker Dooperon 04/28/2019

The Isle of Wight - as seen through Windowson 08/10/2017

The Isle of Wight - as seen through Windowson 08/10/2017

Turning the Mattresson 10/27/2015

Turning the Mattresson 10/27/2015

The Last Voyage of the Mirabitaon 08/24/2015

The Last Voyage of the Mirabitaon 08/24/2015

Comments

Wow! What a great deal of research has gone into this article, Jan, but with your usual efficiency the joins don't show! I knew nothing about boxing in earlier centuries but now I feel I can hold forth with confidence on the subject, thanks to a brilliant article. Have you got any more photographs? I feel it would benefit from one or two to break up the text.